This article was published more than 5 years ago.

This article is part of a series featuring inspiring stories of local action #fromthefrontlines of COVID-19 in the Global South. For more, visit our COVID-19 page and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has exposed glaring shortcomings in healthcare around the world. From the United States, where a shortage of personal protective equipment has endangered frontline health workers, to Nigeria, where the government is attempting to force through draconian legislation that would allow police to detain anyone suspected of being sick, consequences of the coronavirus’s rapid spread have shone a spotlight on the rampant inequalities in public health.

In response, Fund-backed organizations are stepping up to ensure that equal access to healthcare is afforded to all people. As watchdogs keeping governments accountable, thought leaders advocating for a more equitable future, and frontline responders providing basic services—or sometimes acting as all three—these local leaders and activists have a critical role to play in improving the world’s neglected public health institutions.

Watchdogs keeping government accountable

Nothing in life is free—but in Kenya, even being quarantined comes with a price. Hundreds of Kenyans, forced into mandatory quarantine in government facilities for breaking curfew or not wearing masks, report that state authorities demanded that they cover all expenses incurred, including food and accommodation.

In response, Muslims for Human Rights (MUHURI), a civil society organization working throughout Kenya’s coastal region, filed a public interest lawsuit against the attorney general, the health minister, and the inspector general of police, demanding that the government cover the cost of quarantine.

“It is common knowledge that the government has received funding from the World Health Organization towards the fight against COVID-19,” MUHURI Chairman Khelef Khalifa wrote in an affidavit. “It has the financial capacity to suppress the virus without forcing its citizens to pay for their upkeep once placed under mandatory quarantine.”

Although the Kenyan government has since backtracked after a mounting public outcry and is no longer requiring those subject to mandatory quarantine to pay for their expenses, major concerns remain about the inadequate and unsanitary conditions of government quarantine sites.

As governments across the globe use the pandemic as pretext to curtail civil liberties and clamp down on human rights, watchdogs like MUHURI are an essential check on state power.

Advocating for a more equitable future

Even as the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, the future looms large—how can health officials prepare for another outbreak or the next crisis?

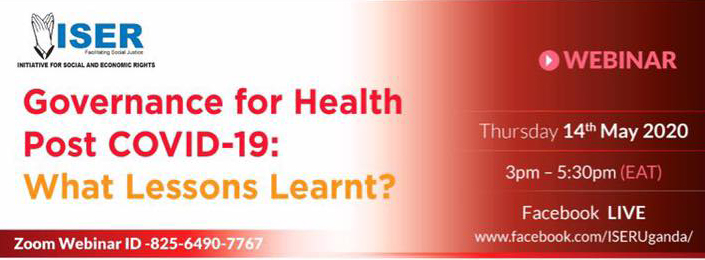

In Uganda, activists from the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) recently held a digital seminar on lessons learned from the country’s experience with COVID-19. Featuring a member of parliament, health officials from different levels of government, and activists from Uganda and abroad, the discussion examined how domestic and international systems can be improved going forward.

ISER has been a critical voice in defending human rights in Uganda during the pandemic. An infographic they produced on maintaining human dignity and respecting rights during COVID-19 outlines several points for strengthening Uganda’s public health system, including adequate financing and continued access for non-COVID patients.

By bringing together government officials and local activists in discussion, ISER is helping to ensure that the needs of all people are represented in policymaking around public health.

Providing for frontline needs

Myanmar’s central government has largely excluded ethnic minorities from their pandemic response, failing to even translate important health information into indigenous languages. To spread awareness and offer relief, local community groups are sharing important information about COVID-19 and delivering basic services to at-risk people.

The Karen Women’s Organization (KWO), a leading indigenous group with over 60,000 members, have visited nearly 2,000 families in need. As policy advocates as well as frontline providers, delivering direct services gives KWO on-the-ground information necessary to make recommendations that meet the needs of the Karen people—one of Myanmar’s ethnic minorities.

More than 70,000 Karen people live in refugee camps in Thailand, and thousands more are internally displaced in Karen areas of Myanmar. A recent military campaign by the Tatamadaw, Myanmar’s armed forces, into a northern district of Karen State has driven hundreds more from their homes.

Without state assistance, KWO has distributed masks to approximately 5,000 people, delivered hygiene products in refugee camps along the border with Thailand, and translated critical information about prevention and protection against COVID-19 into the Karen language. As frontline responders, their work is vital to ensuring the health and safety of vulnerable minority communities in Myanmar.