This article was published more than 4 years ago.

James Logan, the Fund’s European office director, and curator Ekow Eshun dialed into Instagram Live last week to discuss their recent collaboration: a London-based photography exhibition called Face to Face. These excerpts from their conversation have been lightly edited for clarity.

People often say that working in the field of human rights “must be quite depressing,” says James. “But it’s not. I get to work and see the most incredible activists, people who are really taking a stand, creating positive change, who get up in the morning and are being creative and really making a difference in the world.”

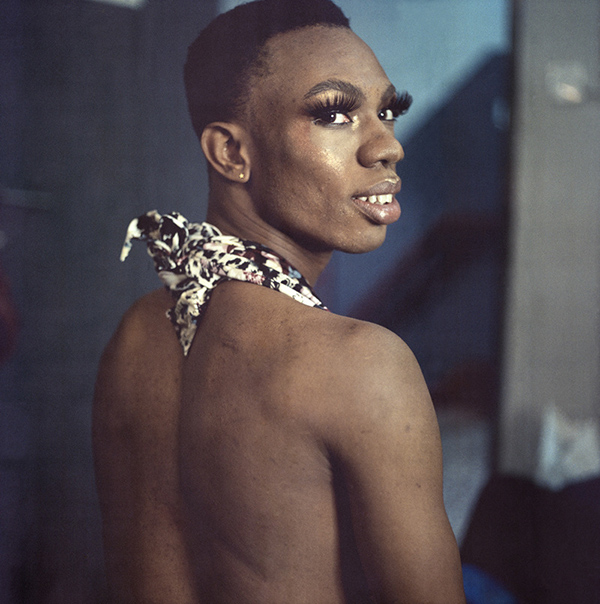

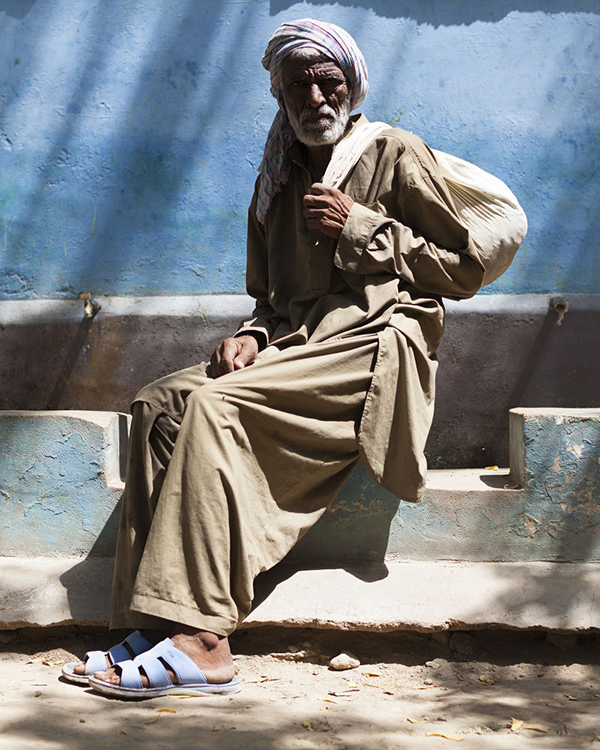

“I see that in some of the pictures in Face to Face,” he adds. “Unlike traditional NGO photography where people are seen as objects of charity, these images show a deeper picture of a community and one in which—in some of those pictures—there’s a lot of hope.”

The Face to Face exhibition presents “photography of nuance or depth, but really of beauty,” Ekow—the exhibition curator—agrees. “You’re allowed to look at pleasurable images, even if they deal with difficult subjects or discomfort or people who are dispossessed. The photos can still be striking, compelling, beguiling, and beautiful.

“You want to get to subjectivity,’ Ekow says. ‘You want to get to empathy, you want to get to human connection. That’s—as I understand it—what you do at the Fund. And I feel that’s what these photographers are dedicated to doing.”

James nods, adding that some of the images he likes most in Face to Face are where the “subjects have actually been involved in the creation of the picture themselves.” Kyle Weeks’ Ovahimba Self Portraits are the obvious examples, where the subjects have control of the camera’s shutter. “It’s having people put themselves in the picture and tell their own stories,” he says.

Not only that, but it’s a way of disrupting certain power dynamics between photographer and subject, Ekow suggests. “The result is stronger, more empathic photography. You want documentary photography to be cognizant of the lives of the people involved in the photo.”

James says he didn’t imagine there would be such a clear connection between the Fund’s activities across the world and the photography exhibition. But it has shown him the power of “letting subjects tell their own stories”—just, as he says, the way “we at the Fund don’t believe in directing people in what they should be doing.”

The experience of collaborating in Face to Face has also shown that “you can send photographers with a broader brief to go and capture images and document what’s going on, but in a way that’s a lot more nuanced and subtle and creative,” says James.

“We sitting here in the West don’t have all the answers for how we construct or consume images of people elsewhere,” Ekow agrees. “The real impetus for me is to keep looking and thinking about how we can better look closer at the lives of others.”

Face to Face is about new ways of finding common ground, understanding one another, and—even over the lo-fi split-screen of Instagram Live—coming together to forge a deeper connection. The exhibition is taking place now in King’s Cross Tunnel and across the King’s Cross site, as part of the Outside Art Project, until November 29.

Discover more about Face to Face by visiting the Face to Face site.